I Was Convinced Nvidia Was the New Cisco. I Was Wrong.

For months, perhaps even a year, I was a card-carrying member of the Nvidia skepticism club. I wasn't just a passive observer; I was an active believer in the bearish case, and I wasn't quiet about it. To me, the writing was on the wall, written in the ink of historical precedent and market logic. I saw the headlines and nodded with a grim sense of intellectual satisfaction. The comparison to Cisco Systems before the dot-com bust wasn't just an analyst's talking point; it was my core thesis. I saw a hardware company, brilliant as it was, caught in a speculative spending frenzy that had a clear expiration date.

Every piece of negative news fit perfectly into my carefully constructed narrative. When I read on Wccftech that OpenAI, the poster child of the AI revolution, was exploring Google's TPUs, I saw the first crack in the fortress. “See?” I’d tell friends, “The lock-in is a myth. Even the biggest customers are balking at the prices.” When Yahoo Finance relentlessly amplified a CFRA analyst's prediction that AMD would 'close the gap' by 2026, it confirmed my belief that Nvidia’s dominance was temporary, its moat shallow. And then came the ultimate validation: the story, pushed heavily by The Motley Fool, that billionaire Philippe Laffont was selling off a massive chunk of his shares. For me, that was it. The smart money was getting out while the getting was good. The party was, unequivocally, ending.

I held onto this belief with the tenacity of someone who feels they've seen the truth behind the curtain. The stock’s relentless climb didn't sway me; it only deepened my conviction that the fall would be that much more spectacular. But a funny thing happens when you wait for a collapse that refuses to arrive. The dissonance between the dire warnings I cherished and the quarterly results that kept shattering expectations began to create a low, persistent hum of cognitive friction.

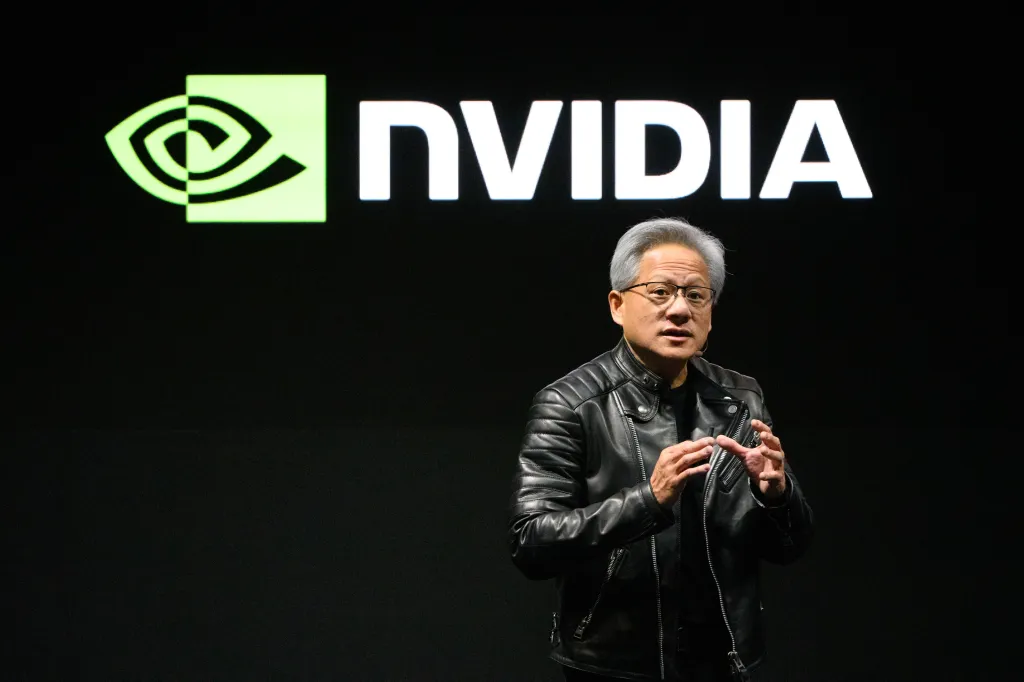

The catalyst for my change of heart wasn't a single headline or a flash of insight. It was a slow, humbling process of intellectual surrender, which began during a deep-dive into an earnings report. It was a throwaway line in the Q&A, where CEO Jensen Huang wasn't just talking about chips, but about a full stack of software, networking, and libraries. He spoke of AI “factories,” and for the first time, I felt a flicker of doubt in my own well-rehearsed cynicism. Was I missing the plot?

My biggest and most cherished argument was the Cisco analogy. It was so elegant, so historically sound. Cisco sold the plumbing—the routers and switches—for the dot-com internet boom. Its stock soared on the belief that the build-out would last forever. When the speculative dot-com companies went bust, the demand for plumbing evaporated, and Cisco’s stock crashed, taking over a decade to recover. I saw Nvidia as the new Cisco, selling the 'shovels'—the GPUs—in this new AI gold rush. The narrative was identical.

But as I began to dig deeper, prompted by that earnings call, I was confronted with a difficult truth: my analogy was fundamentally lazy. The dot-com bubble was built on speculation—on business models that promised to monetize 'eyeballs' and 'clicks' in a far-off future. The AI revolution is different. The 'gold' being mined today isn't speculative; it's tangible. It's accelerating drug discovery at pharmaceutical companies, creating logistics efficiencies that save billions, powering autonomous systems, and enabling scientific breakthroughs in climate modeling and fusion energy. Unlike the dot-coms, Nvidia’s customers are the largest and most profitable companies in the world, and they are deploying AI not out of speculation, but because it is already generating massive productivity gains and revenue. I had been comparing a company fueling a speculative bubble to one fueling a tangible industrial revolution. Nvidia isn't just selling the shovels; it’s selling the entire automated mining facility, complete with the power plant, the robotic workforce, and the operating system that runs it all. The comparison wasn’t just wrong; it was a fundamental misreading of the entire technological era.

This realization forced me to re-examine my other certainties. I had bought into the idea that AMD was on the verge of 'closing the gap.' It’s a classic two-horse race narrative. But I was thinking about it in terms of hardware specifications, a chip-versus-chip battle. My mistake was ignoring the ecosystem. I started to understand CUDA, Nvidia's software platform. It's a programming language, a set of libraries, and a developer environment that has been the standard for accelerated computing for over 15 years. Millions of developers are trained on it; a vast universe of scientific and AI applications are built on it. AMD making a competitive chip is like a new company manufacturing a high-quality gasoline engine. Nvidia isn't just selling the engine; it's selling the car, the global network of gas stations and mechanics, and it taught the entire world how to drive. The gap isn't a hardware spec that can be closed in one generation; it's a deep, entrenched platform advantage that is years, if not a decade, ahead.

Then I had to confront the OpenAI story and my belief that Nvidia's pricing power was fragile. I saw it as a simple cost-cutting measure. But I failed to see the strategic calculation. For a company like OpenAI or its competitors, the single greatest cost is not the price of a GPU; it's the cost of time. The time it takes to train a new, larger model is the difference between leading the industry and falling behind. While alternatives exist and are used for less intensive tasks (inference), for cutting-edge training where speed is paramount, Nvidia's integrated platform provides a performance advantage that translates directly into a competitive advantage. The premium price isn't a bug; it's a feature. It's the price you pay to be first. My view was that of a consumer looking at a price tag, not a strategist looking at a time-to-market calculation.

Finally, I had to revisit the 'smart money' narrative of Philippe Laffont's stock sale. The headline was powerful: Billionaire Sells 1.4 Million Nvidia Shares. That’s the story I told myself. But I had never bothered to look at the SEC filing itself. When I finally did, I found the story wasn't what I thought. Yes, his fund, Coatue Management, sold 1.4 million shares. But after that sale, it still held over 3.6 million shares, a position worth billions. This wasn't a panicked sprint for the exit. This was a fund manager, after a historic, life-changing run-up in a single stock, taking a small percentage of profits off the table to manage risk. It was prudent portfolio management, not a vote of no confidence. I had been duped by a simple narrative because it fit the story I wanted to believe.

I am not here to tell you that Nvidia is without risk or that its valuation is eternally justified. My crystal ball is as cloudy as anyone else’s. But I am here to confess that my previous skepticism was built on a foundation of shallow analogies and incomplete information. I was so focused on finding the historical pattern that I failed to see the novelty of the moment. I mistook a foundational technology shift for just another cyclical boom. It's a humbling thing to admit you were wrong, especially when you were so certain. But my journey from skeptic to believer has taught me one thing: in a revolution, looking at the past isn't always the best way to see the future.