Anatomy of a Flawed Bear Case: Deconstructing the Hysteria Against Nvidia

A chorus of sophisticated-sounding skepticism has recently coalesced around Nvidia, attempting to construct a narrative of impending doom from a handful of carefully selected data points. The arguments, repeated with increasing fervor across financial media and tech blogs, center on three core claims: that a key customer is diversifying, that executive stock sales signal a lack of faith, and that the company is merely a temporary tool-maker in the grand AI gold rush. However, a clinical examination of these core arguments reveals a foundation built not on sound analysis, but on a series of logical fallacies, convenient omissions, and a fundamental misreading of the technology landscape. It is time to dissect these claims and expose them for the intellectual vaporware they are.

The 'Indispensability' Straw Man: A Deliberate Misreading of Market Dominance

The first pillar of the anti-Nvidia thesis rests on reports, most prominently from TechPowerUp, that OpenAI is utilizing Google's TPUs for a portion of its inference workloads. This, the critics contend, is the fatal crack in the armor, proof that Nvidia is not indispensable. This argument is a textbook example of a 'straw man' fallacy combined with a 'false dichotomy.' It constructs an absurd standard of 'total indispensability'—implying that any customer using any competitor's product for any reason signifies a catastrophic failure—and then attacks that fabricated standard.

Let's be intellectually honest. The AI market is not a monolith; it is a complex ecosystem of distinct workloads. Training massive, next-generation foundation models is a fundamentally different task than running inference on an already-trained model at the lowest possible cost per query. Nvidia's platform, centered on its CUDA software stack and state-of-the-art GPUs, remains the undisputed global standard for the former. The world's most advanced AI research and development happens on Nvidia. That is not a narrative; it is a verifiable fact.

For a hyperscale customer like OpenAI, which serves billions of queries, it is not just rational but a basic tenet of operational resilience to diversify its supply chain for high-volume, cost-sensitive workloads like inference. To expect a single-vendor strategy at that scale is commercially naive. The real question is not, "Is OpenAI using a competitor?" The real questions, which critics conveniently ignore, are: "What platform is OpenAI using to train GPT-5 and beyond?" and "What percentage of the exploding AI infrastructure market does Nvidia continue to capture?"

The fact that a customer is optimizing a specific part of its cost structure does not negate the value of the platform that enables their core innovation. The argument is a non-sequitur. It's like arguing that because a Formula 1 team uses a Ford truck to transport its race car, the Ferrari engine inside is suddenly irrelevant. The hysteria over TPU adoption is a tactical distraction from the strategic reality: the AI revolution is being architected, trained, and overwhelmingly deployed on Nvidia's full-stack platform.

The Fallacy of Ominous Portents: Misinterpreting Executive Stock Sales

The second argument, a recurring headline about insider stock sales surpassing $1 billion, is perhaps the most intellectually dishonest of the three. It relies on innuendo and an appeal to motive, presenting routine financial management as a clandestine signal of impending collapse. This narrative deliberately omits crucial context to foster suspicion.

The vast majority of these sales are conducted under pre-scheduled Rule 10b5-1 trading plans, which are established by executives months in advance precisely to avoid any suggestion of trading on non-public information. These are not panicked-button sales; they are automated, planned liquidations for purposes of diversification, tax planning, and philanthropic endeavors. To frame this as a 'red flag' regarding leadership's confidence is a fallacious leap of logic.

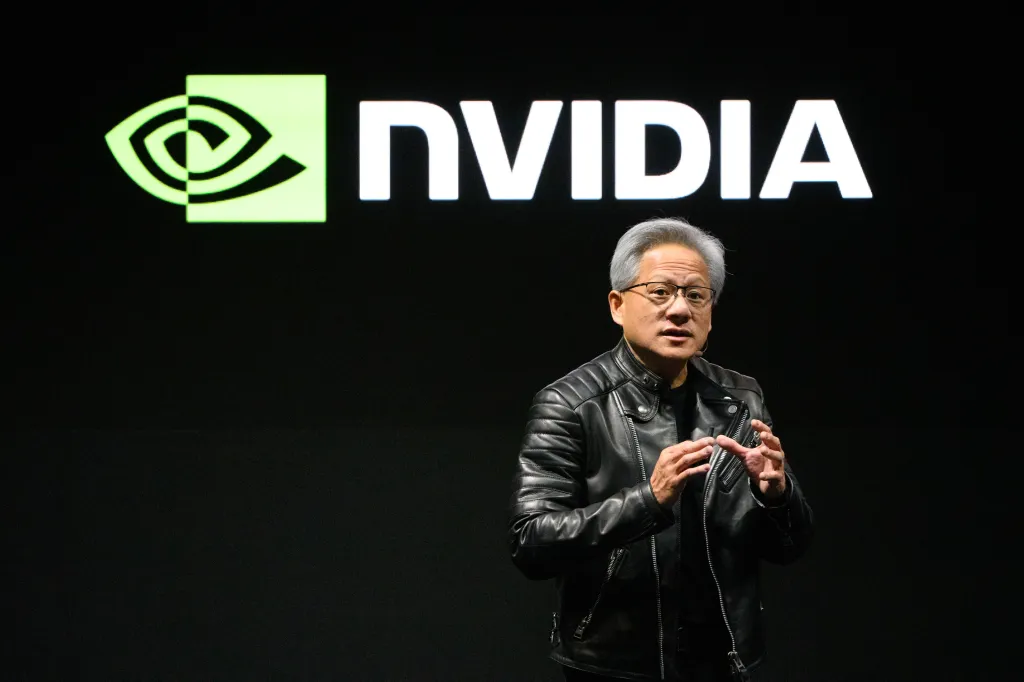

The real evidence of leadership's confidence is not found in their personal portfolio management, but in their corporate actions. Confidence is demonstrated by launching generational products like Blackwell. Confidence is signing massive enterprise partnerships with giants like HPE. Confidence is investing billions to expand the supply chain with partners like Wistron. Confidence is CEO Jensen Huang articulating a clear, multi-trillion-dollar vision for the future of accelerated computing and AI factories. To ignore these monumental signals of strategic conviction in favor of speculating about an executive's need to diversify their wealth is to prefer gossip over analysis.

Contrasting the $1 billion in sales against the trillions in shareholder value created under this same leadership exposes the argument's absurdity. The focus on sales is a transparent attempt to create fear where no rational basis for it exists.

The 'Picks and Shovels' Non-Sequitur: A Failure to Grasp Value Creation

Finally, we have the counter-narrative, championed by figures like Masayoshi Son, that Nvidia is merely selling 'picks and shovels' in the AI gold rush and will not be the ultimate victor. This analogy is not just tired; it's fundamentally flawed and reveals a deep misunderstanding of the modern technology stack.

In the 19th-century gold rush, picks and shovels were simple, commoditized tools used to extract a finite resource. In the 21st-century AI revolution, Nvidia's platform is not a simple tool; it is the integrated, full-stack factory that creates the gold. The CUDA ecosystem, with its decades of development and millions of developers, is the operating system for AI. It is the foundational layer upon which all subsequent value—from OpenAI's models to every enterprise AI application—is built.

To argue that the application layer (the 'gold') will capture all the value while the enabling platform (the 'factory') becomes a commodity is a non-sequitur. It is like suggesting that Microsoft in the 1990s was just a 'picks and shovels' company for application developers. History shows that the owner of the dominant, defensible platform often captures the most significant and durable value. Nvidia is not just selling silicon; it is selling a continuously compounding competitive advantage in the form of its software ecosystem.

Betting on OpenAI over Nvidia is not a mutually exclusive proposition; it's an intellectually inconsistent one. OpenAI's very existence and future progress are contingent on the computational power that Nvidia's roadmap provides. One cannot exist without the other, but only one provides the fundamental, horizontal platform that powers the entire industry.

When the emotionally charged narratives are stripped away, the case against Nvidia collapses under the weight of its own logical fallacies. The bear case is built on a straw man of indispensability, the innuendo of insider sales, and a flawed industrial-era analogy. The reality, grounded in evidence of market share, strategic partnerships, and an unparalleled software moat, remains unchanged. Nvidia is not simply a participant in the AI revolution; it is its prime architect, and any analysis that fails to grasp this central truth is not analysis at all—it is merely noise.